YouTube processes more than 3 billion searches per month, making it the second-most-used search platform in the world. Accessing this data can reveal rising trends, competitor patterns, and new opportunities for content creation. The challenge is that collecting this information requires dealing with YouTube’s robust anti-bot systems and other technical barriers. This guide walks you through reliable methods for gathering YouTube search data at scale and helps you choose the method that best fits your goals.

What data can be extracted from YouTube search results

Here are the main types of data you can pull from a YouTube search results page. These details are extremely useful for audience research, search optimization, and understanding your competitors’ strategies.

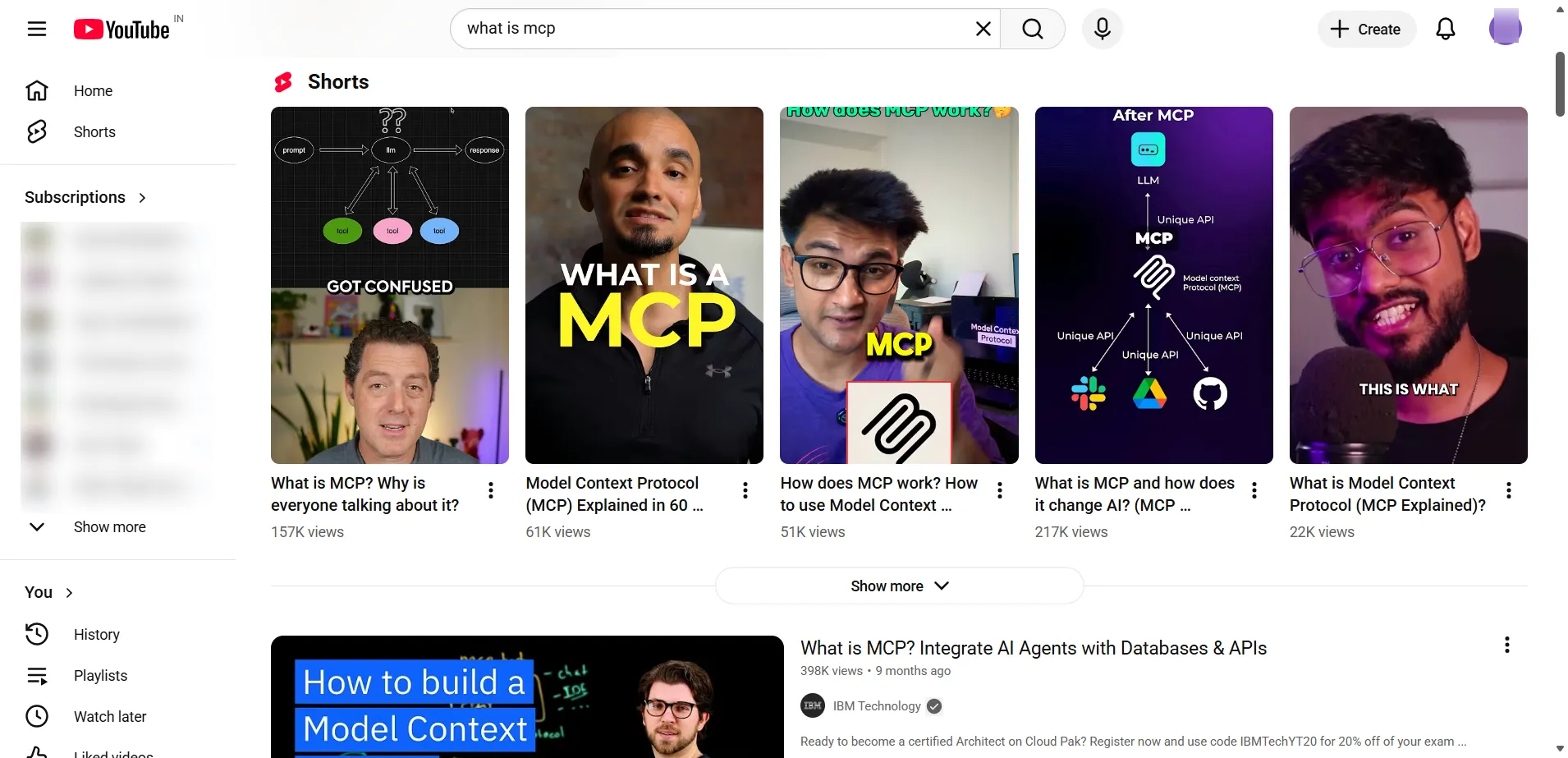

Here is an example of a YouTube results page for the query “what is mcp”, showing the main pieces of information that can be captured during extraction:

The most useful data you can extract includes:

- Video title and link. This gives you the video’s main topic and the direct URL, both crucial for keyword research and topic discovery.

- Channel name and channel link. This shows who published the content and helps you study competitors or identify potential creators to collaborate with.

- View numbers. These figures reflect how much attention a topic is getting and how strong the demand is.

- Publish date. Knowing when a video was uploaded helps you separate long-lasting content from new and fast-growing subjects.

- Video length. Duration offers insight into what format your audience prefers, whether short explanations or more detailed guides.

- Description preview. The short text excerpt beneath the title often contains important keywords and context.

- Thumbnail link. The preview image URL is helpful for studying visual styles, branding cues, and click-through patterns.

Collecting this information at scale enables you to answer key questions, such as which topics are gaining attention, what phrasing high-ranking channels use, and how long the average video is in your category.

Methods for scraping YouTube search results

There are three main approaches to collecting data from YouTube. The option you choose depends on how often you need the data, how complex your project is, and how much technical work you want to take on.

The first method is using the YouTube Data API. This is Google’s official solution, so it is stable and returns neatly formatted JSON responses. However, it comes with very tight daily limits. On the free tier, you can make only about 100 search requests per day, and not all publicly visible information is included. This method is generally suitable for smaller projects, academic use, or any scenario where you only need occasional data.

The second method is direct web scraping. This gives you full freedom to collect any data displayed on the page without worrying about API restrictions. The downside is that it is considerably more technical. You need to handle browser automation, proxy rotation, JavaScript rendering, and frequent updates to bypass YouTube’s anti-bot systems. This option is best suited for developers who need very specific data fields and are comfortable managing their own scraping setup.

The third method is using a Web Scraping API. These services handle the difficult parts for you, including CAPTCHA, proxy management, and JavaScript loading. They offer very high reliability and scale well. The tradeoff is the subscription cost and reliance on a third-party provider. This approach is ideal for companies or developers who want dependable, large-scale data extraction without maintaining the underlying scraping infrastructure.

Step-by-step guide to scraping YouTube search results with Python

If you want full control over your data collection process, creating your own Python scraper is a strong option. In this walkthrough, we will look at two popular choices. The first is yt dlp, which quickly extracts video metadata without loading a browser. The second is Playwright, which uses real browser automation and is useful for handling complex or dynamic YouTube pages.

If you are completely new to scraping, you may want to read our detailed Python scraping guide before continuing.

Scraping with the yt dlp library

yt-dlp is a Python tool and command-line program derived from the Youtube dl project. While many people use it for downloading videos, it can also pull metadata directly in JSON format. It is fast, lightweight, and works without spinning up an actual browser.

Step 1 Install yt dlp

Prepare your working environment by entering the following commands in your terminal:

# Create and activate a virtual environment

python -m venv youtube-scraper

source youtube-scraper/bin/activate # macOS/Linux# OR (Windows)

.\youtube-scraper\Scripts\activate.bat # Windows CMD

.\youtube-scraper\Scripts\Activate.ps1 # Windows PowerShell# Install yt-dlp

pip install yt-dlp

Step 2 run the scraper script

Below is the complete Python script that performs a YouTube search for a keyword and saves the retrieved details, including title, view count, likes, duration, and more, into a well-structured JSON file.

import json

import sys

from typing import Any, Dict, List, Optionalfrom yt_dlp import YoutubeDL

from yt_dlp.utils import DownloadError# Configuration constants – modify these to change search behavior

SEARCH_QUERY = “what is mcp”

SEARCH_RESULTS_LIMIT = 10# yt-dlp configuration (suppresses output and returns JSON)

YDL_OPTS = {

“quiet”: True,

“no_warnings”: True,

“dump_single_json”: True,

}def normalize_video_info(info: Dict[str, Any]) -> Dict[str, Any]:

“””Convert YouTube’s API response to a standardized format.”””

# Convert duration from seconds to MM:SS format

duration = info.get(“duration”, 0)

formatted_duration = f”{duration // 60}:{duration % 60:02d}” if duration else “N/A”# Parse YouTube’s upload date (YYYYMMDD) to standard date format

upload_date = info.get(“upload_date”)

create_time = None

if upload_date:

try:

create_time = f”{upload_date[:4]}-{upload_date[4:6]}-{upload_date[6:8]}”

except (IndexError, TypeError):

create_time = upload_datereturn {

# Core video metadata

“id”: info.get(“id”),

“url”: info.get(“webpage_url”),

“title”: info.get(“title”),

“description”: info.get(“description”),

# Engagement metrics

“view_count”: info.get(“view_count”),

“like_count”: info.get(“like_count”),

“comment_count”: info.get(“comment_count”),

# Channel information

“username”: info.get(“uploader”),

“user_id”: info.get(“channel_id”),

“follower_count”: info.get(“channel_follower_count”),

“is_verified”: info.get(“channel_is_verified”),

# Temporal data

“create_time”: create_time,

“duration”: duration,

“duration_formatted”: formatted_duration,

# Content classification

“hashtag_names”: info.get(“tags”, []),

“language”: info.get(“language”),

# Thumbnail should be last as it’s often the longest value

“cover_image_url”: info.get(“thumbnail”),

}def search_youtube(query: str, limit: Optional[int] = None) -> List[Dict[str, Any]]:

“””Search YouTube using yt-dlp’s internal search functionality.”””

# ytsearchX: prefix tells yt-dlp to return X search results

search_url = f”ytsearch{limit if limit is not None else ”}:{query}”with YoutubeDL(YDL_OPTS) as ydl:

try:

results = ydl.extract_info(search_url, download=False)

return (

[

normalize_video_info(entry)

for entry in results.get(“entries”, [])

if entry # Skip None/empty entries

]

if results

else []

)

except DownloadError as e:

print(f”Search error for query ‘{query}’: {e}”, file=sys.stderr)

return []def save_results_to_json(data: List[Dict[str, Any]], filename: str) -> None:

“””Save data to JSON file with proper error handling.”””

if not data:

print(“No data to save.”, file=sys.stderr)

returntry:

with open(filename, “w”, encoding=”utf-8″) as f:

json.dump(data, f, indent=4, ensure_ascii=False)

print(f”Successfully saved {len(data)} results to {filename}”)

except IOError as e:

print(f”Error saving results to {filename}: {e}”, file=sys.stderr)def main() -> None:

“””Main execution flow: search -> process -> save results.”””

print(f”Searching YouTube for ‘{SEARCH_QUERY}’…”)search_results = search_youtube(SEARCH_QUERY, SEARCH_RESULTS_LIMIT)

if search_results:

filename = “youtube_search.json”

save_results_to_json(search_results, filename)# Print summary of first 5 results

print(f”\nFound {len(search_results)} results:”)

for i, video in enumerate(search_results[:5], 1):

print(f”{i}. {video[‘title’]} – {video[‘username’]}”)if len(search_results) > 5:

print(f”… and {len(search_results) – 5} more results”)

else:

print(“No results found.”)if __name__ == “__main__”:

main()

The behavior of the script is controlled by two key settings at the top:

SEARCH_QUERY defines the keyword or phrase used to look up videos on YouTube.

SEARCH_RESULTS_LIMIT sets the maximum number of results the script returns.

Next, here is what the yt dlp configuration options mean:

- “quiet”: True keeps the console output clean by hiding progress indicators and status messages.

- “no_warnings”: True prevents small or unimportant warnings from appearing.

- “dump_single_json”: True instructs yt dlp to skip downloading the actual video and instead collect all available metadata into one JSON response.

When the script finishes running, it creates a file named youtube_search.json that contains all the extracted information. Below is an example of what that output looks like, with the description text shortened for readability.

{

“id”: “eur8dUO9mvE”,

“url”: “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eur8dUO9mvE”,

“title”: “What is MCP? Integrate AI Agents with Databases & APIs”,

“description”: “Ready to become a certified Architect on Cloud Pak? Register now… Dive into the world of Model Context Protocol and learn how to seamlessly connect AI agents to databases, APIs, and more. Roy Derks breaks down its components, from hosts to servers, and showcases real-world applications. Gain the knowledge to revolutionize your AI projects…”,

“view_count”: 205371,

“like_count”: 4914,

“comment_count”: 137,

“username”: “IBM Technology”,

“user_id”: “UCKWaEZ-_VweaEx1j62do_vQ”,

“follower_count”: 1240000,

“is_verified”: true,

“create_time”: “2025-02-19”,

“duration”: 226,

“duration_formatted”: “3:46”,

“hashtag_names”: [“IBM”, “IBM Cloud”],

“language”: null,

“cover_image_url”: “https://i.ytimg.com/vi/eur8dUO9mvE/maxresdefault.jpg”

}

The real reason this method doesn’t deliver

Although YtDLP is excellent for quick data extraction, it is not the most reliable solution for consistent, large-scale scraping. There are a few reasons for this:

- It can easily break. Since the tool relies on YouTube’s internal structure, any change on YouTube’s side can cause failures. Your scraper stops working until the community updates the project.

- Rate limits appear quickly. Sending too many requests in a short period often results in HTTP 429 responses. Without proper retry delays or pacing, the script will repeatedly fail.

- IP blocking is common. Collecting a significant amount of data from a single IP address can result in HTTP 403 errors, often displayed as “Video unavailable.” Using rotating residential proxies helps reduce this risk.

Using internal API endpoints for scraping

To begin, you need to locate the API request YouTube uses for its search results:

- Open your browser’s developer tools. You can do this by right-clicking the page, selecting Inspect, and then switching to the Network section.

- Filter the list to show only XHR or Fetch calls, then refresh the page.

- Look for the request whose URL ends with search?prettyPrint=false.

- Open that request and check the Payload tab. From there, you can copy the clientVersion value that YouTube sends.

The POST request depends on a specific JSON body. Below is the simplest required structure:

{

“context”: {

“client”: {

“clientName”: “WEB”,

“clientVersion”: “2.20250620.01.00”,

“hl”: “en”,

“gl”: “US”

}

},

“query”: “your search term”

}

The request body includes several important fields:

- clientName should remain set to “WEB”

- clientVersion must match the value you copied from DevTools, since YouTube updates it frequently

- query is the phrase you want to search for

- hl sets the interface language

- gl defines the country code YouTube should use

- userAgent should match the user agent string from your own browser

Step 1 install the requests library if it is not already available

If you do not have the requests package installed, add it with:

pip install requests

Step 2 run the scraper script

import json

import requestsclass YouTubeSearcher:

def __init__(self):

# YouTube internal search API endpoint

self.url = “https://www.youtube.com/youtubei/v1/search”# Basic client context so requests look like they come from a real browser

self.context = {

“client”: {

“clientName”: “WEB”,

“clientVersion”: “2.20250620.01.00”,

}

}def search(self, query: str, max_videos: int = 20):

“””Run a YouTube search and return a list of video dictionaries.”””

videos = []

continuation = None # Token for loading the next page

seen_ids = set() # Track IDs to avoid duplicates# Keep fetching pages until we reach the requested number of videos

while len(videos) < max_videos:

payload = {

“context”: self.context,

“query”: query,

}if continuation:

payload[“continuation”] = continuationtry:

# Send POST request with a timeout

response = requests.post(self.url, json=payload, timeout=10)

data = response.json()new_videos = self._get_videos(data)

# Remove duplicates based on video ID

unique_videos = []

for video in new_videos:

if video[“id”] not in seen_ids:

seen_ids.add(video[“id”])

unique_videos.append(video)# Add new unique results

videos.extend(unique_videos)# Get token for the next page of results

continuation = self._get_continuation(data)# Stop when there are no more pages or nothing new

if not continuation or not unique_videos:

breakexcept Exception as e:

print(f”Request failed: {e}”)

breakif not videos:

print(“No videos found for this query”)return videos[:max_videos]

def _get_videos(self, data):

“””Collect all video entries from a single API response.”””

videos = []

self._find_videos(data, videos)

return videosdef _find_videos(self, obj, videos):

“””Walk through the nested response and locate videoRenderer objects.”””

if isinstance(obj, dict):

if “videoRenderer” in obj:

video = self._parse_video(obj[“videoRenderer”])

if video:

videos.append(video)

else:

for value in obj.values():

self._find_videos(value, videos)elif isinstance(obj, list):

for item in obj:

self._find_videos(item, videos)def _parse_video(self, renderer):

“””Convert a single videoRenderer node into a flat video dict.”””

try:def text(node):

“””Helper for pulling readable text from YouTube text objects.”””

if not node:

return “”

if “simpleText” in node:

return node[“simpleText”]

if “runs” in node and node[“runs”]:

return node[“runs”][0].get(“text”, “”)

return “”# Core fields

video_id = renderer.get(“videoId”, “”)

title = text(renderer.get(“title”))

channel = text(renderer.get(“longBylineText”))

views = text(renderer.get(“viewCountText”))

duration = text(renderer.get(“lengthText”))

published = text(renderer.get(“publishedTimeText”))# Best thumbnail (last one is usually highest resolution)

thumbnail = “”

if “thumbnail” in renderer and “thumbnails” in renderer[“thumbnail”]:

thumbs = renderer[“thumbnail”][“thumbnails”]

if thumbs:

thumbnail = thumbs[-1].get(“url”, “”)# Short description snippet (first detailedMetadataSnippets entry)

description = “”

if (

“detailedMetadataSnippets” in renderer

and renderer[“detailedMetadataSnippets”]

):

snippet = renderer[“detailedMetadataSnippets”][0]

if “snippetText” in snippet and “runs” in snippet[“snippetText”]:

parts = [

run.get(“text”, “”)

for run in snippet[“snippetText”][“runs”]

]

description = “”.join(parts)[:200] # Trim to 200 charsreturn {

“id”: video_id,

“title”: title or “No title”,

“url”: f”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v={video_id}”,

“channel”: channel or “Unknown”,

“views”: views or “No views”,

“duration”: duration or “Unknown”,

“published”: published or “Unknown”,

“thumbnail”: thumbnail,

“description”: description,

}except Exception as e:

print(f”Failed to parse video: {e}”)

return Nonedef _get_continuation(self, obj):

“””Extract the continuation token used to fetch the next page.”””

if isinstance(obj, dict):

if (

“continuationCommand” in obj

and “token” in obj[“continuationCommand”]

):

return obj[“continuationCommand”][“token”]for value in obj.values():

result = self._get_continuation(value)

if result:

return resultelif isinstance(obj, list):

for item in obj:

result = self._get_continuation(item)

if result:

return resultreturn None

def save(self, videos, filename: str = “youtube_search.json”):

“””Write video data to a JSON file with UTF 8 encoding.”””

with open(filename, “w”, encoding=”utf-8″) as f:

json.dump(videos, f, indent=2, ensure_ascii=False)

print(f”Saved {len(videos)} videos”)# Example usage

if __name__ == “__main__”:

searcher = YouTubeSearcher()

results = searcher.search(“what is mcp”, 10)

searcher.save(results)

To run this code, you call the search method with your search phrase as the query argument and, if you want, a numeric max_videos value to cap how many results are returned.

This is what goes on backstage:

- YouTube sends back a continuation token, and the loop keeps requesting new pages until it has collected enough videos or there are no more results to load.

- A recursive walk through the response looks for every videoRenderer object and pulls out the videoId, title, view text, duration, publish time text, thumbnail URL, and a short slice of the description.

- A set of seen IDs is maintained so that the same video is not added more than once across different pages.

When the script finishes, it writes everything to a JSON file. Each video entry in that file follows a neat, structured shape similar to this:

{

“id”: “eur8dUO9mvE”,

“title”: “What is MCP? Integrate AI Agents with Databases & APIs”,

“url”: “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eur8dUO9mvE”,

“channel”: “IBM Technology”,

“views”: “205,576 views”,

“duration”: “3:46”,

“published”: “4 months ago”,

“thumbnail”: “https://i.ytimg.com/vi/eur8dUO9mvE/hq720.jpg?sqp=-oaymwEXCNAFEJQDSFryq4qpAwkIARUAAIhCGAE=&rs=AOn4CLBXBwZNQuJ5lEfpsX5wQrJ9SjHPvg”,

“description”: “Unlock the secrets of MCP! Dive into the world of Model Context Protocol and learn how to seamlessly connect AI agents to …”

}

Scraping with Playwright

If the methods described earlier do not give you enough control, you can switch to a full browser approach and imitate a real visitor. YouTube search pages are heavily driven by JavaScript, which means results appear through dynamic loading, infinite scroll, and live changes to the page structure. To handle all of that reliably, you need a tool that works in a real browser environment.

Step 1 install Playwright

# Install the library

pip install playwright# Download browser binaries (Chromium, Firefox, WebKit)

playwright install

Step 2 scrape the search results

The idea is straightforward. First, you open the search results page in a browser session, then keep scrolling down. Each scroll action prompts YouTube to load more videos, and you repeat this until you have gathered enough results. For every video block on the page (ytd-video-renderer elements), read the metadata by selecting the appropriate CSS targets and pulling out the details you need.

The script below handles the entire scraping workflow automatically:

import asyncio # Async support for browser actions

import json # Exporting scraped data to a JSON file

import logging # Simple logging for progress and errors

from datetime import datetime # Timestamping the output

from urllib.parse import quote # Safely encoding the search term in the URLfrom playwright.async_api import async_playwright # Playwright async browser API

# Configuration

SEARCH_QUERY = “what is mcp”

OUTPUT_FILE = “YT_search_results.json”

MAX_RESULTS = 3

HEADLESS = True

SCROLL_DELAY = 2.0

MAX_IDLE_SCROLLS = 3logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.INFO,

format=”%(asctime)s – %(levelname)s – %(message)s”,

)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)async def get_element_data(element, selector: str, attribute: str | None = None) -> str:

“””Safely read text content or an attribute from a matching child element.”””

try:

sub_element = await element.query_selector(selector)

if not sub_element:

return “”if attribute:

value = await sub_element.get_attribute(attribute)

return value or “”text = await sub_element.text_content()

return text.strip() if text else “”

except Exception:

return “”def parse_number_with_suffix(text: str | None) -> int:

“””

Convert compact numeric strings into integers.Handles:

– Durations like ‘5:30’ (returns seconds as an integer)

– View counts like ‘1.2M’, ‘3.4K’

“””

if not text:

return 0text = text.lower().strip()

# Duration case (e.g., ‘5:30’)

if “:” in text:

clean_text = “”.join(c for c in text if c.isdigit() or c == “:”)

if “:” in clean_text:

try:

parts = [int(p) for p in clean_text.split(“:”) if p]

# Rightmost part is seconds, then minutes, then hours, etc.

return sum(part * (60 ** i) for i, part in enumerate(reversed(parts)))

except Exception:

return 0# View count case (e.g., ‘1.2M views’)

text = text.replace(“views”, “”).strip()

multipliers = {“k”: 1_000, “m”: 1_000_000, “b”: 1_000_000_000}for suffix, multiplier in multipliers.items():

if suffix in text:

try:

return int(float(text.replace(suffix, “”)) * multiplier)

except Exception:

return 0try:

return int(float(text))

except Exception:

return 0async def extract_video_data(element) -> dict:

“””Pull all relevant fields for a single video item.”””

title = await get_element_data(element, “a#video-title”)

url_path = await get_element_data(element, “a#video-title”, “href”)metadata_items = await element.query_selector_all(“#metadata-line .inline-metadata-item”)

views_text = “”

upload_time = “”try:

for item in metadata_items:

raw = await item.text_content()

text = raw.strip() if raw else “”

if “view” in text.lower():

views_text = text

elif text:

upload_time = text

except Exception:

passduration_text = await get_element_data(

element,

“ytd-thumbnail-overlay-time-status-renderer span”,

)channel_name = await get_element_data(element, “#channel-name a”)

channel_path = await get_element_data(element, “#channel-name a”, “href”)return {

“title”: title,

“url”: f”https://www.youtube.com{url_path.split(‘&pp=’)[0]}” if url_path else “”,

“views”: parse_number_with_suffix(views_text),

“upload_time”: upload_time,

“duration_seconds”: parse_number_with_suffix(duration_text),

“channel”: channel_name,

“channel_url”: f”https://www.youtube.com{channel_path}” if channel_path else “”,

“thumbnail”: await get_element_data(element, “yt-image img”, “src”),

“verified”: (await element.query_selector(“.badge-style-type-verified”)) is not None,

}async def load_videos(page, max_results: int | None) -> list:

“””

Scroll the search results page and collect video elements.Stops when:

– No new videos appear after several scrolls

– Or max_results has been reached

“””

logger.info(“Loading videos…”)

videos: list = []

idle_count = 0while True:

current_videos = await page.query_selector_all(“ytd-video-renderer”)if len(current_videos) > len(videos):

videos = current_videos

idle_count = 0

logger.info(“Found %d videos”, len(videos))

else:

idle_count += 1

if idle_count >= MAX_IDLE_SCROLLS:

breakif max_results and len(videos) >= max_results:

videos = videos[:max_results]

breakawait page.evaluate(“window.scrollTo(0, document.documentElement.scrollHeight)”)

await page.wait_for_timeout(int(SCROLL_DELAY * 1000))return videos

async def scrape_youtube(query: str, max_results: int | None) -> dict | None:

“””Open the search page, scroll, extract all video data, and save the result.”””

url = f”https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query={quote(query)}”async with async_playwright() as p:

browser = await p.chromium.launch(headless=HEADLESS)

page = await browser.new_page()try:

logger.info(“Scraping query: %s”, query)

await page.goto(url, wait_until=”domcontentloaded”, timeout=60_000)# Handle cookie banners if they appear

cookie_btn = page.locator(

‘button:has-text(“Accept all”), button:has-text(“I agree”)’

)

if await cookie_btn.count() > 0:

await cookie_btn.first.click()await page.wait_for_selector(“ytd-video-renderer”, timeout=15_000)

video_elements = await load_videos(page, max_results)

logger.info(“Extracting data from %d videos…”, len(video_elements))videos_data = await asyncio.gather(

*[extract_video_data(v) for v in video_elements]

)result = {

“search_query”: query,

“total_videos”: len(videos_data),

“timestamp”: datetime.now().isoformat(),

“videos”: videos_data,

}with open(OUTPUT_FILE, “w”, encoding=”utf-8″) as f:

json.dump(result, f, indent=2, ensure_ascii=False)logger.info(“Saved %d videos to %s”, len(videos_data), OUTPUT_FILE)

return resultexcept Exception as e:

logger.error(“Error during scraping: %s”, e)

try:

await page.screenshot(path=”error.png”)

except Exception:

logger.error(“Failed to capture error screenshot”)

return None

finally:

await browser.close()async def main() -> None:

“””Entry point for the async scraper.”””

result = await scrape_youtube(SEARCH_QUERY, MAX_RESULTS)

if not result:

logger.warning(“Scraping did not return any data”)if __name__ == “__main__”:

asyncio.run(main())

To adjust how the scraper behaves, you only need to modify a few constants at the top of the script:

- SEARCH_QUERY defines the keyword or phrase you want to look up.

- OUTPUT_FILE sets where the final JSON data will be saved.

- MAX_RESULTS determines how many videos should be collected before stopping.

- HEADLESS, SCROLL_DELAY, and MAX_IDLE_SCROLLS control whether the browser is visible, how fast the page scrolls, and when the scraper should stop if no new results appear.

For every video block on the page, the script extracts the title, link, view count, upload time, length in seconds, channel name, channel link, the thumbnail source, and whether the channel is verified.

After running the scraper, it produces a YT_search_results.json file. A single entry in that file will look like this:

{

“search_query”: “what is mcp”,

“total_videos”: 3,

“timestamp”: “2025-06-16T18:13:25.825228”,

“videos”: [

{

“title”: “Model Context Protocol (MCP), Clearly Explained (Why it Matters)”,

“url”: “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3MX7HoGXug”,

“views”: 54000,

“upload_time”: “1 month ago”,

“duration_seconds”: 639,

“channel”: “Builders Central”,

“channel_url”: “https://www.youtube.com/@BuildersCentral”,

“thumbnail”: “https://i.ytimg.com/vi/e3MX7HoGXug/hq720.jpg?sqp=-oaymwEnCNAFEJQDSFryq4qpAxkIARUAAIhCGAHYAQHiAQoIGBACGAY4AUAB&rs=AOn4CLAYrFn7Oy46CcQ-VhPrAa4Q9kSOGw”,

“verified”: false

},

{

“title”: “What is MCP? Integrate AI Agents with Databases & APIs”,

“url”: “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eur8dUO9mvE”,

“views”: 195000,

“upload_time”: “3 months ago”,

“duration_seconds”: 226,

“channel”: “IBM Technology”,

“channel_url”: “https://www.youtube.com/@IBMTechnology”,

“thumbnail”: “https://i.ytimg.com/vi/eur8dUO9mvE/hq720.jpg?sqp=-oaymwEnCNAFEJQDSFryq4qpAxkIARUAAIhCGAHYAQHiAQoIGBACGAY4AUAB&rs=AOn4CLBwIHe-26ZrIPVZPSkmAswm1cD0aQ”,

“verified”: true

},

…,

…

]

}

Handling challenges and anti-bot systems

Even the most carefully built custom scraper will eventually run into YouTube’s protection mechanisms. Some of the main obstacles include:

- IP throttling and temporary bans. Sending too many requests from the same address can trigger blocks, errors, or CAPTCHA challenges very quickly.

- CAPTCHAs. Once your traffic looks automated, Google will present reCAPTCHA, which is extremely difficult for scripts or headless browsers to bypass.

- Browser fingerprint checks. YouTube can inspect dozens of tiny details about your browser environment—including fonts, graphics output, device characteristics, and plugin behavior- to determine whether the visitor is a human or an automated tool such as Playwright.

- Frequent interface updates. The platform regularly adjusts CSS, HTML structure, and overall layout. Small changes can break your selectors, causing your scraper to stop working until you update the code.

Dealing with all of this requires more than just a basic script. Scalable scraping demands rotating IPs, CAPTCHA solving, and ongoing updates. For real production workloads, maintaining a homemade scraper becomes a continuous effort.

Adding proxies to a custom scraper

A reliable way to avoid IP blocking is to use rotating residential proxies. These offer several advantages when scraping YouTube:

- Distribute traffic across many IP addresses to avoid throttling

- Access regional content by switching locations

- Lower the chance of being flagged as automated

- Make large-scale scraping safer by reducing the risk of IP bans

For dependable, high-volume operations, it’s worth using dedicated YouTube proxy networks such as Decodo.

If you want to use Decodo’s residential proxies in your Python scraper, the first step is to configure the proxy inside your class initializer.

Step 1 set up the proxy details inside your class initializer:

self.proxies = {

“http”: “http://YOUR_USERNAME:YOUR_PASSWORD@gate.decodo.com:7000”,

“https”: “http://YOUR_USERNAME:YOUR_PASSWORD@gate.decodo.com:7000”

}

Step 2 apply the proxy settings to every request inside your search method:

response = requests.post(

self.url,

json=payload,

timeout=10,

proxies=self.proxies, # add this line

verify=False # include this if you want to skip SSL verification

)

That’s all you need to do. If you are scraping with Playwright instead, you can set the proxy when launching the browser like this:

browser = await p.chromium.launch(

headless=HEADLESS,

proxy={

“server”: “http://gate.decodo.com:7000”,

“username”: “YOUR_USERNAME”,

“password”: “YOUR_PASSWORD”

}

)

Simply replace YOUR_USERNAME and YOUR_PASSWORD with the login details provided by Decodo.

The scalable solution using a Web Scraping API

Once manual scraping approaches start breaking too often or require more upkeep than they’re worth, switching to a dedicated scraping API becomes the smarter option. Decodo provides a full scraping infrastructure that handles all the difficult parts automatically, letting you focus entirely on the data you want to collect.

With Decodo, you don’t have to manage headless browsers, rotate proxies, or troubleshoot anti-bot issues. You send a single API request, and the platform handles everything behind the scenes.

Some key advantages include:

- A large pool of rotating residential IPs to prevent bans

- AI-driven anti-bot handling that bypasses CAPTCHA and fingerprint checks

- Automatic JavaScript rendering for dynamic pages

- High reliability with a pay only for successful requests model

Another bonus is that every new user gets a 7-day free trial, allowing you to test YouTube scraping or any other site before choosing a plan.

Setup steps

To start using the Web Scraping API:

- Sign in to your Decodo account or create a new one.

- Choose a plan from the Scraping APIs section (Core or Advanced).

- Activate your trial: each plan includes a 7-day free trial.

- Pick the tool you want to use (Web Core or Web Advanced).

- Paste the YouTube page URL you want to scrape.

- Optionally adjust API settings, including JavaScript rendering, custom headers, location targeting, and more. You can view all available parameters in the documentation.

- Send the request, and in a few seconds you’ll receive a clean HTML response that you can parse or process as needed.

You can also copy an automatically generated code snippet in cURL, Node, or Python. Here’s one example:

import requests

url = “https://scraper-api.decodo.com/v2/scrape”

payload = {

“url”: “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFu9aKJoqGg”,

“headless”: “html”

}headers = {

“accept”: “application/json”,

“content-type”: “application/json”,

“authorization”: “Basic DECODO_AUTH_TOKEN”,

}response = requests.post(url, json=payload, headers=headers)

with open(“youtube_video_data.html”, “w”, encoding=”utf-8″) as file:

file.write(response.text)print(“Response saved to youtube_video_data.html”)

Here’s what this snippet is doing behind the scenes:

- It specifies the Decodo scraping endpoint.

- It adds the YouTube page you want to scrape to the request payload.

- It includes your authentication token in the request headers.

- It sends the API call and stores the returned HTML in a file on your machine.

Remember to swap DECODO_AUTH_TOKEN with the actual token from your Decodo dashboard.

Using dedicated YouTube scrapers

If you prefer an even easier workflow, Decodo also provides purpose-built YouTube scrapers that return ready-to-use JSON—so there’s no need for HTML parsing or manual extraction.

YouTube metadata scraper

This tool delivers rich metadata for any YouTube video. All you need to do is enter the video ID into the dashboard, select YouTube Metadata Scraper as the target, and submit the request. You’ll receive clean, structured JSON instantly.

Below is a sample response you might receive, shortened for clarity:

{

“video_id”: “dFu9aKJoqGg”,

“title”: “What is Decodo? (Formerly Smartproxy)”,

“description”: “Tired of CAPTCHAs and IP blocks? Meet Decodo – the most efficient platform to test, launch, and scale your web data projects.”,

“uploader”: “Decodo (formerly Smartproxy)”,

“uploader_id”: “@decodo_official”,

“upload_date”: “20250423”,

“duration”: 96,

“view_count”: 9081,

“like_count”: 12,

“comment_count”: 4,

“categories”: [“Science & Technology”],

“tags”: [

“decodo”,

“smartproxy”,

“smartdaili”,

“what is smartproxy”,

“proxy network”,

“data collection tool”,

“best proxy network”

],

“is_live”: false

}

YouTube transcript scraper

You can also fetch the complete transcript for a video in any supported language. In the dashboard, choose YouTube Transcript Scraper as the target, enter the video ID in the query field, and set your desired language code.

Below is a sample transcript response, shortened for readability:

[

{

“start_ms”: 80,

“end_ms”: 2560,

“start_time”: “0:00”,

“text”: “ever tried gathering online data only to”

},

{

“start_ms”: 2560,

“end_ms”: 5120,

“start_time”: “0:02”,

“text”: “hit a wall of captures and IP blocks or”

},

{

“start_ms”: 5120,

“end_ms”: 7600,

“start_time”: “0:05”,

“text”: “paid for proxies that barely work it’s”

},

{

“start_ms”: 7600,

“end_ms”: 10080,

“start_time”: “0:07”,

“text”: “frustrating timeconuming and let’s be”

},

{

“start_ms”: 10080,

“end_ms”: 12960,

“start_time”: “0:10”,

“text”: “real a waste of resources why compromise”

}

]

For more complex workflows and additional sample code, you can browse the full Web Scraping API documentation.

Use cases and Applications.

Collecting YouTube search data opens up a wide range of opportunities for creators, analysts, marketers, and developers. Here are some of the most impactful ways to put that data to work:

AI model development. You can assemble datasets for language models, recommendation engines, and content-classification systems. Titles, descriptions, and other metadata provide strong training signals for understanding patterns, predicting engagement, and modeling user intent.

Content strategy and SEO optimization. Studying top-ranking videos helps you see what makes them perform so well. By tracking the keywords and phrasing that consistently attract views, you can identify rising topics and refine your own titles. For instance, if the leading videos for “what is MCP” frequently include phrases like “for beginners,” adopting similar wording might improve your visibility.

Competitor research. Pulling titles, view numbers, and channel details lets you map out which creators dominate your space. This makes it easier to identify coverage gaps, often revealing content ideas with strong potential and little competition.

Trend analysis. Regularly scraping results allows you to detect emerging themes early. Sudden jumps in views or the appearance of new keywords in search titles can signal topics about to gain traction.

Market insights. Engagement metrics, such as likes and comment counts, give you a quick read on audience sentiment. Examining comments on popular review videos, for example, can highlight what users appreciate or dislike about a product.

Final Word

So which approach is best for scraping YouTube? The answer depends on the scope and complexity of your project. Basic scripts work well when you’re starting out, but as your needs expand, dealing with CAPTCHA, rotating IPs, browser automation, and broken selectors becomes increasingly time-consuming.

Scalable tools like Decodo’s Web Scraping API solve those challenges for you, letting you request data with a single call and receive structured output within seconds. With a strong scraping setup in place, you can consistently extract meaningful insights from YouTube and use that information to refine your strategy and stay ahead of the competition.